A SHORT HISTORY OF THE RAILWAYS IN

1876-2007

I would thank Nigel Hatch who helped me with the translation of this article into English.

Also many

thanks to Helena Bunijevac(Railway-Museum,

I: Introduction.

Dalmatia (now part of

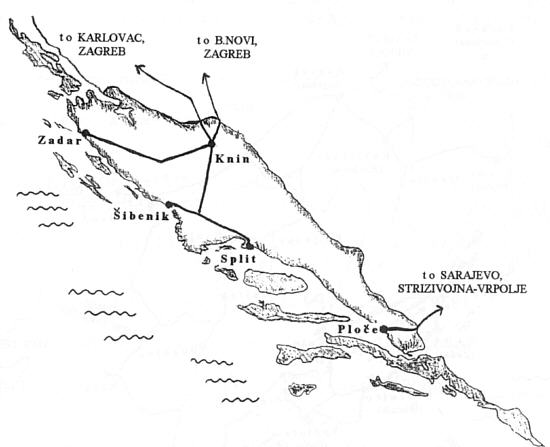

The railway-system of today:

Copyright: Elmar Oberegger

In the past, the

Development of

railways in

Even by the end of

the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918 the provincial capital, Zadar, had no

rail link. The difficulty was that, during this time, it was not possible to

build a railway to the centre of

The railway-system of

Copyright: Elmar Oberegger

At this time,

II: The long way to

1876 and the first railway in

Projects for

railways in

1. Trieste-Fiume(now

2. Split-Livno area-Beograd(Anton Bajamonti, mayor of Split, 1862)

3.

Zadar-Knin-Osijek(City of

4. Karlovac(in the Lika district)-Knin-Split/Sibenik(Bernhard von Wullerstorf-Urbair, Austrian Minister of Trade, 1866)

5. Split-Novi Sad-Budapest(Earl Eugen Zichy, 1868)

6. Construction of a Dalmatian network(Ralph Earle)

7.

8.

In 1866 the

Austrian Government began to mark out several rail routes in

Throughout the

Empire, railway development had been opened to private enterprise since

1854, though it seemed that the Government looked favourably on a projected

route through the

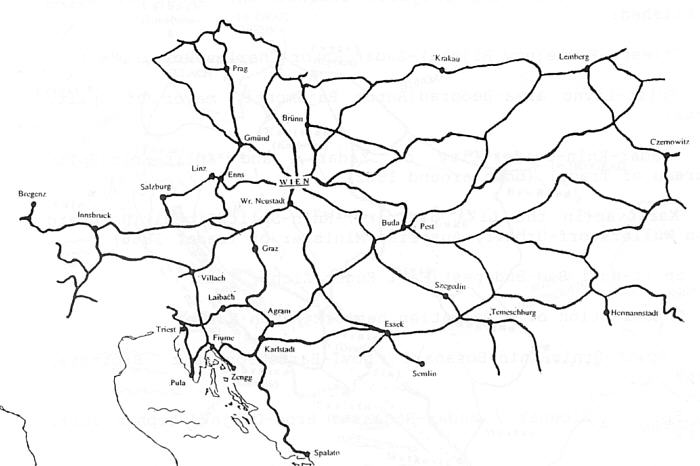

At about the same time, Commodore Bernhard von Wüllerstorf-Urbair, the Austrian Minister of Trade, included the Lika route in his great memorandum "Ein Eisenbahnnetz fur die osterreichische Monarchie" of 1866. The title of this document means "A Railway Network for the Austrian Empire". His concept was very ambitious, but excluded Bosnia-Hercegovina, which was not part of the Empire at the time.

The “Reichsbahn-Konzept”(1866) of Wüllerstorf-Urbair):

Copyright: Elmar Oberegger

In 1867, the year

of the “Ausgleich”, von Wüllerstorf-Urbair retired from politics altogether.

Born in

In 1869, the route Split - Knin - Austro-Hungarian frontier - Lika district - Austro-Hungarian frontier was included in the draft of the Austrian Railway Network Law, but this was only a declaration of intent, as finance remained unobtainable. In the meantime, fresh proposals were published, as follows:

1. Split-Sisak-Barcs, including branches from Knin to Sibenik and Zadar, from Otocac to Senj, and from Ogulin to Brod(Mayor Bajamonti's group)

2. Opuzen (in the Neretva valley) - into Bosnia-Hercegovina(Stephan Türr)

3. Construction of

a Dalmatian network(City of

4. Korinth and the

Adriatic coast to the border of

In 1871, the

Austrian Government put forward a plan to build a main line from

In 1873, the Empire suffered a great economic crisis, and private capital became very scarce. It became clear that the major private investors were not interested in Dalmatian railway projects, as the region had little natural wealth.

In the same year,

the railway from

A new Austrian

state railway policy now developed, which lasted until the end of the First

World War. The full Lika railway project was beyond their financial

capacity, but a start was made on this strategic link. Construction began in

1874, and the line from

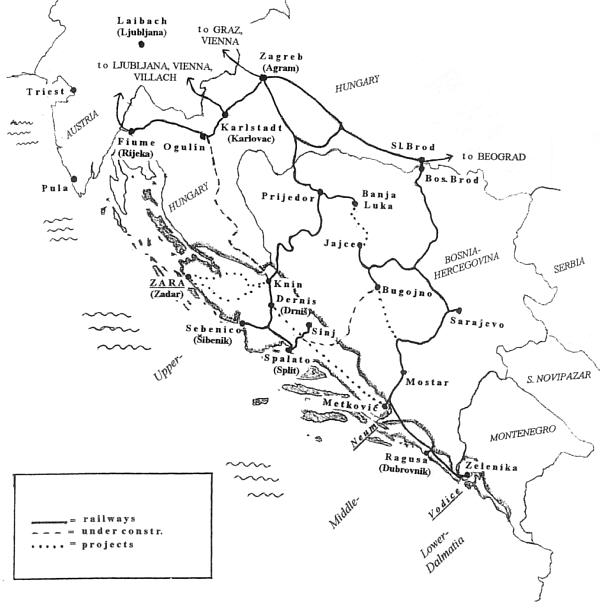

The “Dalmatinerbahn”:

Copyright: Elmar Oberegger

III: Later projects.

In 1878, Bosnia-Hercegovina

was occupied by the Austro-Hungarian Army. The first requirement for both

the Austrian and Hungarian Governments was to develop this former Ottoman

territory economically. A suitable railway system was seen as an essential

part of this policy, particularly to link it to the coast of the

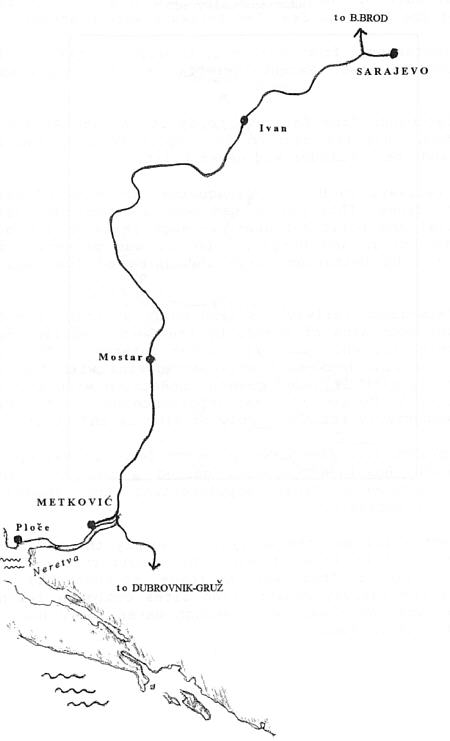

1. The Narentabahn,

from

The “Narenta-/Neretvabahn”:

Copyright: Elmar Oberegger

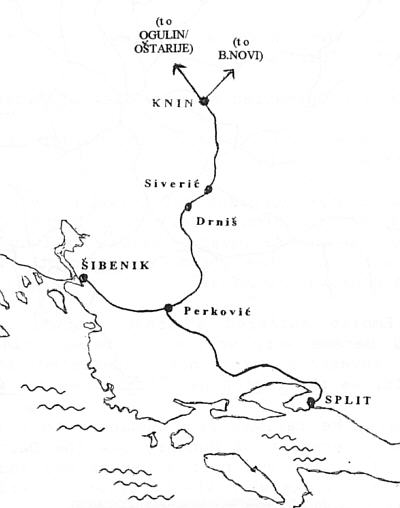

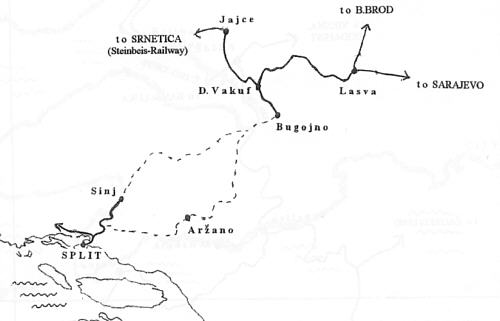

2. The Spalatobahn, from

The “Spalatobahn”:

Copyright: Elmar Oberegger

Like other railways

in Bosnia-Hercegovina, these were narrow-gauge (76cm) lines. This policy had

been adopted for reasons both financial and political. Narrow-gauge railways

are quick and cheap to build, and

A private 76cm-gauge railway was also built at

this time from Knin into the mountains of

The “Steinbeisbahn”:

Copyright: Elmar Oberegger

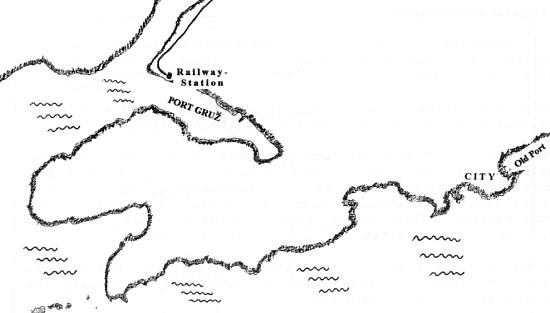

In 1901, a branch from the Narentabahn to Zelenica was opened. From a branch, Bosnia-Hercegovina gained a new rail-linked harbour at Dubrovnik Gruz, supplementing the inadequate harbour at Port Metkovic.

Port Dubrovnik Gruz:

Copyright: Elmar Oberegger

More important still was the ability to supply the naval base at Kotor overland in time of war. The construction of this railway was difficult. There were no roads, so these had to be built before the railway construction sites could be reached. And all the time there was never enough water, only heat and grilling hot rock in summer.

The “Zelenikabahn”:

Copyright: Elmar Oberegger

IV: Projects before

the

In 1914, before the War started, there were the following projected railways:

1. Connection of the capital, Zadar, with the rest of the system. Two lines were planned, one through Obrovac, and the other through Benkovac.

2. A 76cm railway

from Drnis to Metkovic, to link the Zelenica railway with the line from Knin

to

Projects in Bosnia-Hercegovina would also have

affected

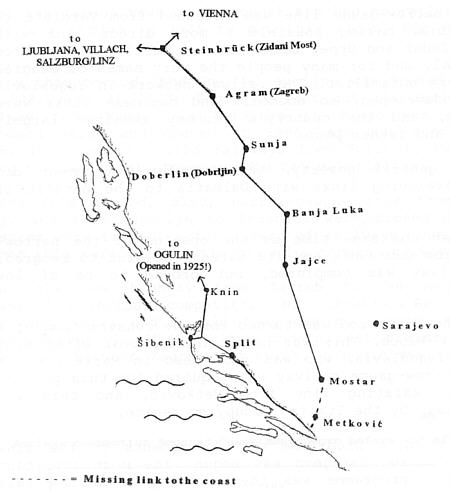

Project Steinbrück(Zid. Most)-Jajce-Mostar:

Copyright: Elmar Oberegger

Dalmatia would also

have benefited from plans to build a new standard gauge line from Doboj to

Samac and to rebuild the narrow-gauge line to

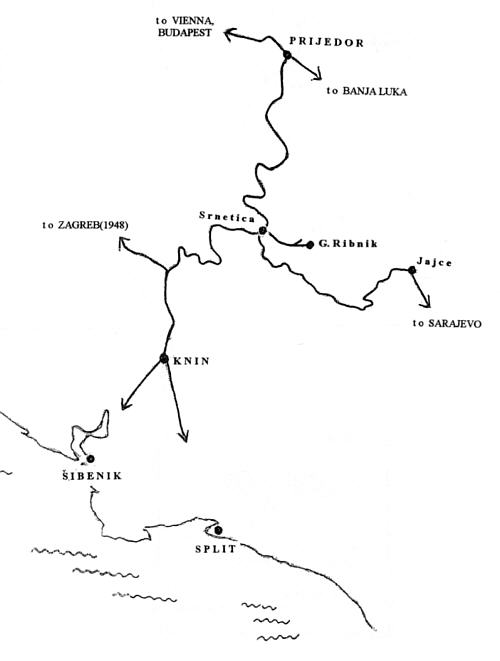

V: Structural Changes since 1918.

Major structural

changes have taken place to the railway system of

Before 1918,

railways had been built according to Austrian interests. A new

standard-gauge line was under construction (the Lika Railway) to link

After the end of

the war Dalmatia was suddenly part of a new nation, the South Slav state of

There was a route

between

By 1925, the

narrow-gauge line was extended from Vardiste to Uzice in

Despite this

general poverty, the Yugoslav Government did succeed in developing links

with

1. In 1925, at the

same time as the opening of the narrow-gauge route from

2. In 1937, the

first sod was turned for the construction of a new seaport at Ploce. This

was named Alexandrovo, after King Alexander of

3. In 1935, also, a

programme of improvements to the line between Metkovic and

4. In 1936,

construction also began of the standard gauge

After the

assumption of power in

The opening of the new railway to Bar affected

the Dalmatian rail system. Up to 1976 traffic between Beograd and the coast

and

Railway-connection Beograd-Adriatic Coast/Montenegro before and after 1976:

Copyright: Elmar Oberegger

This rail route now

became redundant and was closed. Since then, the famous town of

During this period,

the

During this period,

also, narrow-gauge lines from

Today the new highway from

VI: Sources.

BUNIJEVAC Helena: Najskuplja zeljeznica na svijetu. In: EuroCity 3 (2003)

BUNIJEVAC Helena a.o.: 120 godina prvih dalmatinskih pruga. –Zagreb 1997.

BUNIJEVAC Helena: Povijest zeleznickih pruga u Dalmaciji. In: EuroCity 2 (2000)

BUNIJEVAC Helena: Zeljeznica koje vise nema. Povijest uskotracne pruge Split-Sinj. In: EuroCity 1 (2005)

BUNIJEVAC Helena: Povijest privih zeljeznickih pruga u Dalmacij. In: EuroCity 2 (2004)

GELCICH Eugen: Handel, Gewerbe und Verkehr. In: Österreich-Ungarn in Wort und Bild 6. –Wien 1892, 342 ff.

HORN Alfred: Die Bahnen in Bosnien und der Herzegowina. –Wien 1964.

KONTA Jgnaz: Geschichte der Eisenbahnen Oesterreichs vom Jahre 1867 bis zur Gegenwart. In: Geschichte der Eisenbahnen der österreichisch-ungarischen Monarchie I/2, 1 ff.

OBEREGGER Elmar: Eisenbahngeschichte Dalmatiens. Ein Grundriß. –Sattledt 2007.

OBEREGGER Elmar: Zur Eisenbahngeschichte des Alpen-Donau-Adria-Raumes. 3 Bde. –Sattledt 2007.(„Port Ploce“, „Plocebahn“, „Dalmatinerbahn“, „Unabahn“, „Likabahn“ a.o.)

PETERMANN Reinhard E.: Dalmatien. –Wien 1911(Ill. Reiseführer auf den k.k. österr. Staatsbahnen).

RÖLL Victor: Österreichische Eisenbahnen. In: Enzyklopädie des Eisenbahnwesens. Hrsg. v. Victor Röll. –Berlin/Wien 1912 ff.

STRACH Hermann: Allgemeine Entwicklungsgeschichte der österreichischen Eisenbahnen seit 1897. In: GDÖUV, 1 ff.

SUNDHAUSSEN Holm: Geschichte Jugoslawiens. –Stuttgart a.o.1982.

VASILJEVIC Sava: Der Transitverkehr durch Jugoslawien und jugoslawische Seehäfen. –Beograd 1984.

WÜLLERSTORF-URBAIR Bernhard: Ein Eisenbahnnetz für die österreichische Monarchie. In: Österreichische Revue 1866, 22 ff.